Note:

Five years ago I wrote an analysis of the exploration in Bethesda’s The Elder Scrolls: Oblivion. For those of you who haven’t played it, it’s like Elder Scrolls: Skyrim but not as user-friendly. It’s pretty cool, but hard to read the way I originally wrote it. I vaguely recall I was swamped at the time, so I probably cut some corners.

So now, five years later, I’m updating the article and making it easier to read. Enjoy (again?).

Summary

One of the coolest things about Oblivion is how “free form” the game feels. As you wander through the world, attempting to do a quest that you have in your log, you are constantly running across other quests, ancient ruins, castles, cave systems, farms, camps, etc…. All of which are inevitably just slightly off your path, and which show up on your radar when you get close.

In studying how they accomplish this feat, I played through a few steps on the “critical path” quest line, as well as some of other the major quest lines in the game.

Using a method I explain below (supplemented with information from gamefaqs.com) I was able to form a picture of some of the main tools Oblivion uses to encourage and teach their core exploration mechanic.

Exploration Tools

- Leveraging the critical path to train exploration

- Often, there are a trail of tempting adventures that lead the player gently off the critical path.

- Leveraging the major quest lines to encourage exploration

- These get you into the cities, which send you out all over the place.

- Using “stub quests” to fill out the world and make more content

- Stubs are short, linear quests with no story (or very little story) attached.

- Using Cities as massive “Quest Hubs”

- The major quest lines often lead you to cities for this reason.

- Good use of landmarks

- Landmarks tempt players to wander off the path just to see what is there.

Methodology

My methods were as follows:

- I never used “quick travel.” I always walked from where I got the quest to the destination

- If I had an option of taking a straight line between two points and following the meandering main roads, I saved the game and did both.

- I attempted to play like an average fairly linear non-completionist player and always took the shortest path to my destination.

- I stopped in towns only if I needed to sell stuff, or if a quest led me there.

- I wandered off the path if something cool came up in my immediate vision.

- I didn’t follow my compass unless I could see what it was indicating from the path.

- I stayed on one quest line at a time and continued to follow it until it was done.

In all cases I noted the following:

- Number and names of quests encountered

- Names of quests that I got which resulted purely from the completion of the quest.

- Names and numbers of dungeons encountered

- Numbers of enemies encountered.

- Any additional notes I thought were worth remembering.

Leveraging the Critical Path

“First” Quest

Oblivion does a number of really slick things with the critical path that I didn’t notice the first time I played this game. These techniques really help to foster and train their exploration mechanic in a very subtle way.

The first two quests on the critical path (“Tutorial” and “Deliver the Amulet”) essentially boil down to the following steps:

- Go through a dungeon, which fills up your inventory. This is so you’ll want to find a store to sell all your stuff.

- Upon exiting the dungeon, you are treated to a forced view of an Ayleid Ruin dungeon a short ways away.

- You are not required to go to this dungeon but it establishes the fact that there are things out there you can explore which are not on the critical path.

- Next you go through the Imperial City (shortest path). At this point, you’re probably desperate to sell things – so the designers included a quest that you can find in almost every shop in the merchant district.

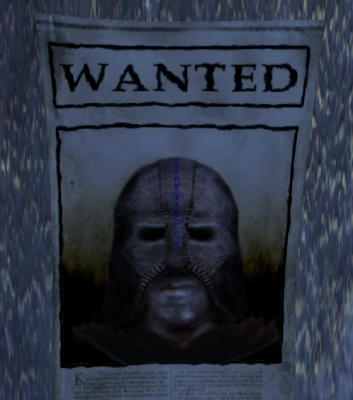

- You are also exposed very quickly to the thieves guild quest (the quest start is on a poster at every gateway into the merchant district and tons of people talk about it).

- After leaving the city, the road leads you near an inn with a guy standing in the middle of the road who has a quest for you. There is also a quest inside the inn. Both of these are almost impossible to miss, and trains the player that he/she can get quests from many NPCs.

- Leads you past a castle-style dungeon that you can see but don’t have to go to. This reinforces #1.

- Right before your destination, the road physically leads you through a castle (and essentially marches you right next to the entrance).

- Before you can exit the castle area you must encounter an NPC that tries to steal money from you (encouraging you to fight him and range all over the area, potentially showing you the dungeon door again).

- You arrive at your destination.

It’s clear from this that the designers are leveraging their critical story quest line to essentially train the player on the exploration mechanic, and they do it without saying anything. They just dangle carrot after carrot in front of you

The way they dangle two dungeons in front of you before they make you walk right up to one is a really great concept. They give you two chances to go off and explore on your own (which I did the first time) before they beat you over the head with a dungeon. It’s pretty clever, if you ask me.

Second Quest

The next quest in the critical Path Line, “Find the Heir,” allows you two different ways to approach it. You can either walk straight there from the location you get the quest (which involves going off-road through a forest and over complex terrain) or you cal walk there along the roads.

I did both and came up with the following results:

Straight Path (off road)

- 4 quests

- 6 dungeons

- 3 castles

- 1 dungeon

- 2 ruins)

- 4 enemies (half of which were found at camps with loot)

Using the Roads

- 1 quest

- 1 city (forced)

- Upon exiting this city, you are forced to encounter an NPC who offers you a quest

- 7 dungeons

- 2 castles

- 3 ruins

- 2 caves

- 12 enemies

Both (after they join up)

- 1 Quest

- 6 Enemies

They were able to leverage this step of the quest to give you a staggering number of exploration chances, and that’s independent of the direction you chose to go.

Cities

Cities are full of NPCs, shops, quest locations, quest givers, and all kinds of fun stuff. Oblivion makes good use of its quests to get the player to spend time in these cities. Further, the loot system encourages players to spend a lot of time in cities selling the loot they’ve gotten from adventuring.

Basically, think of the Cities as quest hubs — lots of quests start in them and lots will take you through them.

Leveraging Other Major Quest Lines

We’ve seen how the designers leveraged the critical path to promote exploration. For the next part of my study, I checked out some of the largest quest lines in the game and examined how they encouraged exploration.

Mage Guild

- Before you are allowed to join the mage guild, you get a quest to visit every city on the map

- Since cities are the MAJOR quest hubs in the game, this is huge.

- Magic item and spell creation

- The player is given the ability to create new magic items and spells using components found in the world (soul gems). This encourages the player to go dungeon-crawling to find more of these.

Arena Challenges

- Near the end of the arena challenges, you get a quest called “Origin of the Grey Prince,” the end of which is a cold-blooded murder of the Arena champion. If the player hasn’t done it already, this spawns the Dark Brotherhood quest line.

Fighters Guild

- Quest-givers are located in three different cities, you spend all your time moving between them. This is another way to encourage you to visit the quest hubs.

Thieves Guild

- 3 quest givers in three cities. Five fences in five cities. Between these eight NPCs and the quests you are given, you are sent to every city on the map at least once. Often more than once.

Dark Brotherhood

- Most of the action takes place in Cheydenhal, which has a TON of quests in it. Many of the assassination quests take you to other cities to kill people.

It seems like the main purpose of the major quests is to expose you to the cities, which is an awesome idea. Also, while trekking to and from the quests associated with these guilds, you will run across a ton of dungeons, enemies, and other quests.

Stubs

Most of the quests in Oblivion are “stubs.” These are one-quest lines that don’t lead to anything else. They also frequently involve travel, asset re-use, and text (rather than VO) to explain the mission.

Examples are any quest where you find a book or a note, or just interact with something or walk into an area. Quests usually involve elements like corpses, books, notes, dungeons (sometimes dungeon retraversals), peoples’ houses, or different uses of existing emergent mechanics (like dodging guards). These quests sometimes tell a story (and have updates to them) and sometimes they don’t.

The really clever thing about stubs is that they make the world seem much more alive, full, and vibrant. They also add extra hours of optional gameplay for a minimal cost, which is always nice.

Landmarks

Walking along roads you’ll see things in the distance (even without the compass, which is a real help). Since they picked Ruins and Castles as two of their three dungeon types, these serve as GREAT landmarks (especially the ruins, since they stand out of the natural environment very well).

One thing I really noticed in Oblivion was that they didn’t always take much advantage of the terrain when placing their landmarks. There were a number of gorgeous valleys and hilltops that would have been perfect for a castle or ruin. The roads would take turns that forced me to look at these empty valleys, and I always thought “man, I wish there were something down there).

2015 Note: They did a lot better with this in The Elder Scrolls: Skyrim, so they must’ve learned their lesson.